On Learning: Knowledge Management

For most knowledge-intensive fields of work, including network engineering, you must learn how to manage vast amounts of information if you wish to progress into more advanced levels. The first two articles in this series discuss creating and reviewing flash cards, which through spaced repetitions lead to dramatically increased knowledge retention. But what about static knowledge at-rest?

Knowledge Management:

Just twenty years ago, resting knowledge would typically consist of multiple shelves of books, and several binders full of notes. Many people still operate this way, and there’s nothing wrong with that if it works, since the goal is to know (retain) and understand (apply) the knowledge, regardless of the methods used. For many people, the sense of touch is conducive to learning, hence the physical books and the “muscle memory” of writing out notes by hand.

As for myself, I have always had a preference for knowledge in digital form. A full bookshelf is great for visitors to say “Wow, you’ve read a lot of books!” But beyond mere trophies, I personally don’t experience the appeal of physical books. Digital books don’t take up space in your residence, you don’t have the hassle of moving them around, and of course the largest gain is searchability.

One of my greatest “career blessings” has been having a subscription to Safari Books Online. I say without hesitation that anyone serious about their career in information technology, whether it be software development, infrastructure, design, or business analytics, should consider getting a subscription. I place this service as the single most important money spent on my personal career development each year. New books are added several times each week, and you are frequently offered early access to books that are still being written. Additionally included are many thousands of books that have been published during the past several years, including the majority of the Cisco Press library. One of the best features is the ability to search across all books in the entire library.

For managing this stockpile of knowledge, Safari’s built-in queuing system let’s you collect books you intend to read, or wish to access frequently. I quickly found this to be unwieldy, with the amount of books that I both wish to read, and reference. I like hierarchies, and the current Safari queue is a flat list. What I do is create a hierarchy of browser bookmarks for all the books I’ve come across that I have read, wish to read, or otherwise wish to be able to quickly reference from. I have about 15 folders containing approximately 250 links to books. The folders I’ve created represent general topics, and the links themselves begin with the year of publication. When I wish to reference a particular book, it is much quicker for me to click on the saved link in my browser.

A second major source of knowledge for me is through other people’s online articles and blog entries. I use Feedly for my aggregator, and I have enough feed subscriptions to where I see approximately 300-400 new titles each day, of which I will actually read an average of ten. The raw number may sound like a lot, but it doesn’t take long to actually go through them. I select articles to read first by title, and then by source. This is why it is important to have a good title when you post something (a skill I am still developing). My logic is that if a title is very interesting, I’ll open it regardless of the source, and if the title is vaguely interesting, I’ll open it if it’s from a source whom I know to produce great content. The rest get filtered through very quickly. If I ever encounter a blog entry that I’ve really enjoyed from someone (usually referenced from Twitter or from someone else’s blog), I add them to my feed.

I then clip the good blog entries into OneNote for potential future reference. I have about 5,000 articles and blog entries saved in my collection. A large portion of them were collected not because I read them, but because I assumed I would reference them someday. For example, a few years ago, if someone posted a great blog entry, I would take the time to clip every blog entry from their site. I eventually realized this is not helpful, and only leads to “digital hoarding”. I think it was due to a Fear Of Missing Out, of which I am still learning to move beyond. Access to Safari helped me out dramatically in that regard, but the realization and correction of those tendencies is what led to the creation of this third part of my series on learning.

Although having an unread article for reference can potentially be valuable in the future, it’s more difficult to reference something if you’ve never read it. That is why I eventually learned to clip only those articles that I’ve actually read and wish to save, or those that I’ve at least skimmed over and may reference again (instead of just blindly clipping everything). When I need to search for something to reference, I found I always start at Google anyway, and if I don’t find what I’m looking for on the first page (and rarely the second), then I’ll do a search across my OneNote library. Based on this realization, I’ve thought about purging all of my saved articles and starting over so that I’ll have a more “curated” collection. On the other hand, I figure I’ve already done the work of collecting the articles, and their contents are only a search away.

Also within my OneNote library are all of the digital notes I’ve taken over the years before my transition to direct notes in Anki. In a way, these notes are sort of like the many unread clipped articles in that there’s a decent chance I may never actually reference them, but I’ve already put the work in to capture them, so they stick around. Additionally, while Anki is great for most learning, sometimes traditional notes are more appropriate. On the rare occasion that I decide to learn via video, I use OneNote to capture both notes and relevant screenshots.

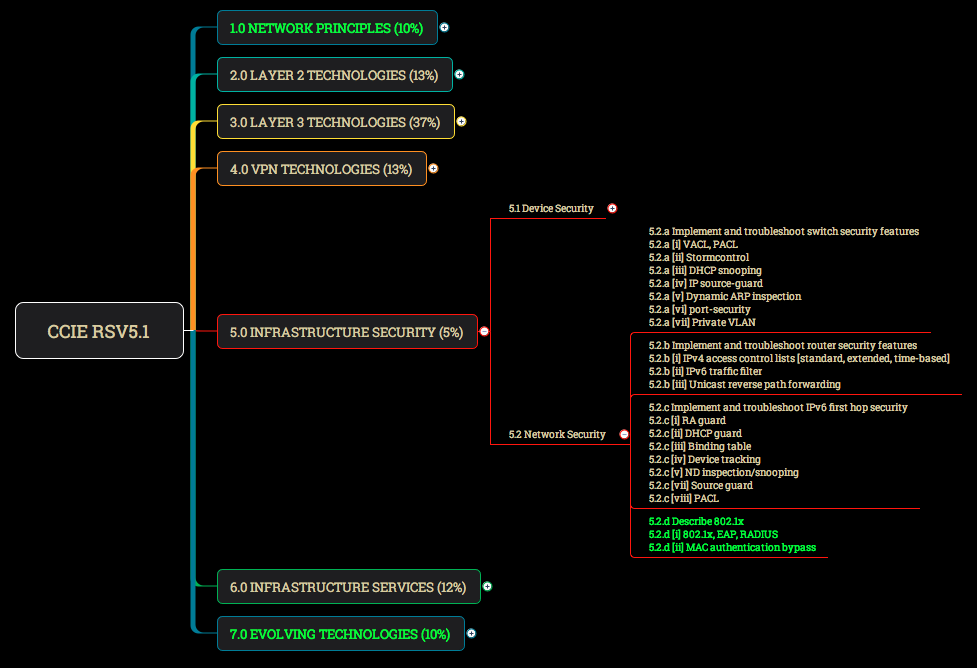

Another tool that has helped me dramatically with knowledge management is something I encountered more recently: Xmind. At its core, Xmind is mind-mapping software, and while it is certainly useful for that in the traditional sense of the term, instead of using it purely as an exploratory mental exercise, I use it mostly to hierarchically organize existing sets of information. This has been extremely powerful with regard to certification studying.

Shown in the above image, I took the CCIE R&S v5.1 blueprint and organized it hierarchically. This allows me to expand or collapse branches of the overall blueprint as desired. Additionally, I colored green those topics which appear on the written exam only, and not on the lab exam. Not shown, I also highlighted sections that I felt were not covered in great depth (or at all) in the OCG books, so that I can quickly see which topics I need to find alternative sources for. Using the same blueprint hierarchy, on another page I broke down each subtopic and wrote a single one-line explanation of the particular technology. For example, “Bidirectional PIM uses only shared trees and is useful when many receivers are also senders.”

Finally, I have been using Xmind as a tool for project management. The paid version of Xmind has a more complete set of traditional project management functions (such as actual time scheduling and tracking), but I use the free version to list tasks I wish to accomplish, and their associated sub-tasks. I then drag and drop the order of the tasks as things change.

I’ve written before how I feel like studying for the CCIE is sort of like a research project. Some people approach it linearly, based on the blueprint. This is sometimes associated with keeping a “tracker”, which is a spreadsheet of topics to study, along with a perceived level of understanding. I’ve tried that approach a couple of times, but it never felt very useful to me personally. Using Xmind, I’ve created a branching tree structure containing things I would like (or need) to do, re-order them as necessary, and cross them off (via strikethrough text) when I have accomplished them. This lets me quickly see where I’ve been and where I intend to go.

Knowledge management is a very subjective topic. To me, learning represents an evolving continuum of progress, and I have tried several different methods of acquiring, maintaining, and managing a base of knowledge over the years. This series represents a set of tools I wish I had known many years ago. Learning is personal, and it takes time to develop the processes that work best for you. As technology continues to evolve, so do the tools and methods of learning, knowledge retention and knowledge management. It can be more difficult to progress if you’re unaware of the available tools and methods. I hope that by sharing my experiences, I may have helped you in some way. Thank you for reading.